- Home

- Maura Weiler

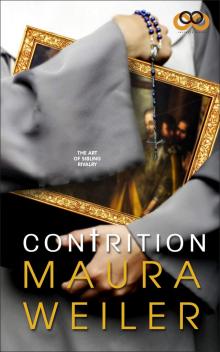

Contrition Page 7

Contrition Read online

Page 7

• • •

Chain-smoking, I chose my streets carefully in South Central. Sister Barbara may have been a fear factor of five, but her convent’s location in an infamous neighborhood bumped my gauge up to ten. Graffiti- covered highway underpasses, boarded-up buildings, and a wailing police siren did little to ease my anxiety.

I pictured the convent as a boxy brick structure with a large cross on the front; similar to church buildings I’d seen in suburban parishes. Instead, the address I’d been given matched a freshly painted, two- story house sandwiched between a liquor store and an empty lot where corroded shopping carts went to die. A barbed wire fence surrounded the house’s quarter-acre of property. I parked on the street, climbed out of my car, and rang the bell.

“You must be Dorie,” said a smiling woman with a salt-and-pepper ponytail after she opened the door. A small, gold cross dangled from a chain over her faded Lakers T-shirt and clay clung to her jeans where she’d wiped her hands. “I’m Sister Barbara.”

“Hello.” I extended my left hand, surprised by the sister’s casual appearance after the habits of the cloistered nuns. The secular clothes made her seem more approachable. “Thank you for seeing me.”

“My pleasure.” Unlike Sister Catherine, Barbara took my hand with her own left and shook it with no excuses or apologies for the clay under her fingernails. “So you want to know what it’s like to be both a Sister and an artist, huh?”

“And how you balance the two.” I nodded.

“Come on back and I’ll show you where I do my dirty work.”

The ceramics studio consisted of a sagging one-car garage that leaned to the left as if whispering a secret to the backyard tomato plants. Inside, clay pots in various stages of completion lined a set of unvarnished shelves. A wheel, a stool, and a kiln shared the floor with a salvaged kitchen cabinet and buckets of water and glaze. A Spanish talk station crackled over a portable radio.

“This is some good stuff.” I wandered from pot to colorful pot. The work was simple and solid.

“Thank you.” Sister Barbara set a lump of clay on the wheel and sat down on the stool. “Basic pieces sell the best—mugs, bowls, and the occasional chalice. The proceeds finance our soup kitchen down the street.”

“Do you make pottery full time?”

“I throw and fire pots in the morning, help my housemates Sister Cindy and Sister Joan serve and clean up lunch for our soup kitchen guests at midday, then come back here to the studio for a couple hours of glazing in the late afternoon.”

“Do you enjoy the work?” I asked, though the care with which Sister Barbara handled her materials had answered my question.

“I love it, sometimes too much. It can be a struggle to keep my pottery within the context of my higher calling to serve God.” Sister Barbara lifted the gold cross that hung around her neck and kissed it. “At one point I gave up pottery for five months because I sensed that it had become too important to me.”

“Wow.” I couldn’t imagine Sister Catherine being able to stop painting for five minutes, much less five months. “How did that go?”

“It wasn’t easy,” Barbara said. “The time away helped me realize that the meditative aspects of pottery-making were integral to my prayer life. But not every artist feels as strongly connected to her work as I do.”

That was true. The stained-glass artist I’d interviewed saw her work as nothing more than a service she was obligated to perform, if not necessarily enjoy, to help support her religious community. The sculptor I’d met was more like Sister Barbara, drawing sustenance from the often tedious, sometimes painful, and occasionally exhilarating artistic process. It fed his soul, and, he admitted, his ego. He had left the priesthood to pursue his sculpting full time.

“I’m no great artist, but people buy it because it’s for a good cause,” Sister Barbara said.

“Are you ever reluctant to sell your art?”

“I keep a couple of things for myself here and there, but generally I try to sell as much as I can.” The sister dipped her hands in a bucket of water and moistened the clay on the wheel. “It’s tough. Sales vary, so I don’t know what our income will be from one month to the next. But between my pottery and donations, Sister Cindy manages to keep the soup kitchen going. Why?”

“The cloistered nun I’m writing the article about refuses to sell her paintings even though I get the feeling her religious community could use the money.”

“Everyone’s situation is different,” the potter said. “Is she fulfilling her regular duties in the convent otherwise?”

“According to the extern sister, she’s doing more than her share.”

“Who pays for her supplies?”

“They’re donated.” I picked up a small, blue pot I particularly liked. “All the nuns are welcome to use them. Or reuse them, in Sister Catherine’s case. She paints over her work to recycle the materials. Do you do that?”

“There’s no reusing clay once it’s fired, but I can’t imagine intentionally ruining something salable.” Sister Barbara spun her wheel via a foot pedal and hunkered down over the lump of soft clay before her. A bowl soon took shape. “What your Sister Catherine does with her paintings is between her and God. Selling the art you produce in your spare time certainly isn’t a requirement in any religious community that I know of.”

“But your pottery—”

“Serves a different purpose. Apostolic orders like mine focus on community outreach. My pottery helps make the soup kitchen possible. A cloistered order focuses on prayer. From what you’ve told me, Catherine’s paintings are a pure form of prayer. Why change what’s working?”

“Is it working?” I frowned, not surprised by Sister Barbara’s answer, but not ready to accept it either. I set the blue pot back on its shelf. The potter saw my expression.

“Sorry to disappoint you, but that’s what I think.” Sister Barbara’s hand slipped and the emerging bowl warped. “Oops.”

The roar of a revving engine followed by squealing tires pierced the dusk.

“You’d better get going.” Sister Barbara wedged the misshapen clay together again and started over. “I don’t want you getting lost around here after dark. Feel free to call or come back anytime if you have more questions.”

I thanked her and drove home.

The sculptor, the stained-glass window maker, and Sister Barbara had all agreed that Catherine wasn’t obligated to show or sell her paintings. Yet each one was more than willing to sell his or her own art. None of them went so far as to destroy good work just to reuse the materials. On that point my twin stood alone.

CHAPTER NINE

On his next day off, Matt powered through his errands so we could visit an illuminated manuscript exhibit at the Getty Museum in the afternoon and catch a Kurosawa film that night.

“It was unnerving,” I said on the tram ride up to the Getty from the parking lot. “The religious artists who aren’t cloistered were really open and friendly. We tabloid journalists aren’t exactly used to being trusted. Not that we should be.”

“I’m sure it helps when they know you aren’t writing an article about them specifically,” Matt said as we arrived at the hilltop museum and exited the tram.

“Yeah, but it makes me want to be worthy of their trust.”

“That’s not a bad thing, is it?”

“Not usually.” I bent down and dipped my hand in the fountain that tripped alongside the museum’s main staircase. “But at The Comet, hyperbole is in my job description.”

“Are the other artists as good as your sister?”

“Nobody is as inspired as Catherine, but some are quite talented. Not one of them was willing to take credit for his or her artwork. Even the sculptor who’d left the priesthood still insisted it was God’s work and he was merely His instrument.”

“Maybe that’s why they’re gifted—God is showing off because He knows He’ll get the acclaim,” Matt said. We reached the Getty’s soaring atrium entrance.

“Nothing like assembling a solid PR team. Singing the boss’s praises can only help their chances of getting into that big studio in the sky,” he added as he opened the door for me.

Inside the illuminated manuscripts exhibit, I marveled over tiny masterpieces wrought on sheepskin by medieval monks. Rich, textured shades of burgundy, azure, salmon, and purple combined in intricate, painstaking patterns to adorn the parchment. Often the borders were even more stunning than the pictures they framed. The violets, poppies, peacock feathers, and dragonflies appeared real enough to be plucked from the page.

“Somebody put a hell of a lot of time into those books,” Matt observed when we wandered the manicured grounds afterward.

“And for what?” I asked. “To be closed up on some shelf for hundreds of years where no one can see them?”

“The manuscript owner saw them, and you’re seeing them now.”

“One page at a time,” I complained.

“Nothing like scarcity to keep you wanting more.” He paused on a garden terrace to take in the expansive view of city and sea as yet another fountain murmured behind us. The late afternoon sun hung over the Pacific like ripe fruit. “Take the Getty here. Limited parking guarantees that it’ll always be a hot ticket. It’s all about marketing.”

“And you can’t beat the admission price.”

I admired the artful combination of stone, water, light, and space at the free museum. Like the cloister, the Getty extended an invitation to slow down, breathe, and appreciate, but I found that hard to do whenever I thought about yet more amazing art going unseen.

• • •

“Okay, fine,” I said over soup and sashimi at Hurry Curry of Tokyo an hour later. Waiters with steaming bowls of noodles slipped smoothly through the narrow aisles without bumping tables or elbows. “I’ll agree that those manuscripts are getting their due in museums now, even if they have been hidden between bindings for centuries. But the thing is, when Catherine paints over an image, that’s it.”

“It’s still there.” Matt sipped his Asahi. “It’s just hidden under a layer of paint instead of a book cover. Painters reuse canvases all the time.”

“Only when they’ve made a mistake or didn’t like the first painting. Nobody paints over a masterwork unless they’re trying to hide it from marauders or something.”

“Which is sort of what Catherine is doing if you think about it,” he said.

“I can’t think about it or I’ll never have the nerve to write the piece.”

“It’s your conscience.” Matt drained his beer and set the bottle back on the table with a thud that reminded me of a judge’s gavel.

It was my conscience, and it was a constant worry. But I wasn’t ready to let go of the opportunity to get to know my sister, much less write a piece that could lead to a real job.

“Anyway, you’re wrong.” I stabbed another piece of sashimi with a chopstick, happy with a one-handed meal that didn’t entail cutting my food. “Catherine paints over them with stuff at least as good. So once she’s covered the original, it’s gone. Nobody’s going to ruin the one on top to get to it.”

“If they really want to see the one underneath, they’ll use an X-ray,” he said.

“It’s not right. She’s doing significant work that should be preserved for posterity. What if great religious artists like Fra Angelico or the monks who illuminated those manuscripts had ruined their own art? There wouldn’t have been anything to exhibit today.”

“And we’d be none the wiser,” Matt said. “Let’s say that your sister is doing significant work. She’s under no more obligation to unleash it on the world than I am to make people read my bad poetry.”

“You write poetry?” I asked.

“I used to when I wasn’t working so much.” Matt gulped a mouthful of noodles.

“I want to read it!” My voice rose an octave.

“You will not be reading it.” He blushed. “Anyway, I threw it out.”

“No, you didn’t.”

“Can we get back to the subject here? Even if Catherine did want to preserve her art, she might not succeed. For all we know, there was a sculptor greater than Michelangelo whose body of work happened to be the victim of a nasty earthquake. Or maybe your sister’s stuff does survive, only to have the fickle art world decide it isn’t all that great in a few years.” Matt pointed his chopsticks at me. “Nobody knows what’s good, what’s bad, or what will last. All we have is right now. And Sister Catherine is living in the now if anybody is. The rest of us should be taking notes.”

“If you believe what you’re saying, why aren’t you shooting your own movie? You have more than enough money saved to make your short.”

Matt put down his chopsticks and wiped his mouth with his napkin. “Touché.”

“I’m sorry, Matt. I didn’t mean to—”

“No, you’re right. You’re absolutely right.” He leaned back in his chair. “I am completely full of shit.”

“At least you’ve got talent. All I’ve got is the desire to capitalize on someone else’s.”

“Uh, uh. You’re not getting away with that. You’re a great writer, and you’re doing what you love for a living, which is more than ninety-nine percent of the population can say. I’m not sure a piece about your sister is the best choice, but I guess you have to follow your gut. Don’t ever lose your passion, Dorie. It’s the best thing about you.” Matt pulled out his wallet as the check arrived. “I’ve got this.”

“Thanks.” I melted, then froze, suspicious. “Okay, what’s going on? You’re buying me dinner and giving me amazing compliments.”

“Is that so unusual?”

“Unusual? It’s unprecedented.”

Matt laughed and paid the bill. “You’ve been so busy researching this story that I hardly see you. I’m just enjoying the time we do have to hang out.”

“I guess there is something to be said for scarcity.” I melted again. “Thanks for dinner.”

As I felt my shoulders relax and ease into the softness of the moment, I watched Matt’s shoulders and jaw contract.

“Yeah, well, don’t think you’re not paying for the movie,” he grumbled with a gruffness that couldn’t negate all the nice things he’d said before.

Matt stood up and strode outside without waiting for me.

I gathered up my coat and reprimanded myself. It wasn’t paying for the movie that bothered me—I had planned to do that anyway. It was falling for the vintage Matt mind game. It had new grass and pretty flowers on it, but it was the same old trap. He’d dangle intimacy in front of me with sweet words and kind gestures, then snatch it away the moment I concluded it was safe to reach for the bait.

For some reason this most recent game didn’t hurt as much as usual. I took my time leaving the restaurant. After all, I had the car keys.

CHAPTER TEN

“The sisters are having a grand, old time with the art supplies you gave us,” Sister Teresa reported when I found her watering the parlor plants on the next Visiting Sunday. “We have lots of new paintings up in the gift shop, thanks to you.”

“But I saw Sister Catherine throw them out,” I said, confused enough to confess I’d been spying.

“She did.” Teresa smiled at my admission. “Since they weren’t hers to dispose of, Mother Benedicta made her retrieve them.”

I hadn’t met Mother Benedicta, but I liked her already. Sister Teresa handed me the narrow watering can through the bars of the parlor grille and pointed to the peace lily behind me.

“Why didn’t Catherine want them?” I doused the plant.

“Oh, she wanted them all right. She wanted them too much.”

I passed the watering can back to Sister Teresa and wrinkled my forehead, mystified.

“Those supplies created a desire in Catherine. A desire she wished to be free of.”

“But is that the right way to avoid temptation—by not exposing yourself to it?”

“Whatever works, I say.” Teresa tipped

the watering can over a ficus. “Is it any more ‘right’ to dangle a chocolate cake in front of someone on a diet?”

Mmmmm, cake. My stomach growled. The night before, I’d spent my grocery money on a room at the nearby inn so I could be at the convent bright and early for services. I reasoned that if Catherine saw me in the chapel, perhaps she’d be more inclined to see me in the parlor. But my twin never once looked up throughout morning prayers. I’d trudged to the visiting room afterward more out of a sense of general optimism than any real belief that she’d appear there.

“Given that I’m the one who led her into temptation, I’m guessing Sister Catherine won’t want to see me today,” I said.

“I’ll tell her that you’re waiting, but don’t expect miracles.”

“I’ll hang around just in case. If there’s anyone else who could use a visitor, I’d love the company.” The journalist in me figured I might as well ask the other nuns about my sister as long as I was there.

“I’ll see who I can rustle up.” Teresa left the room.

I wanted a cigarette but was hesitant to go outside to smoke. What if Catherine came in and didn’t find me? I tried to rid myself of the desire and unwrapped a stick of gum instead. Admittedly, I didn’t try as hard to avoid temptation as Catherine had—I stopped short of throwing away the pack.

The visiting room seemed larger without Sister Carmella’s extended family. Their absence left the sun free to slide around the grille and paint a grid of light and shadow on the now-visible hardwood floor. A small, brown bird trilled on a branch right outside the open window. Even if I didn’t see Catherine, this silent, sunny space wasn’t a bad place to spend the day. I pulled out a new notebook and wrote down the observations I’d compiled on the cloister and my sibling.

Shortly after noon, I ate the granola bar I’d discovered at the bottom of my purse and opened a novel. Before I found my place, Sister Teresa returned with a young Filipina woman. I recognized her as the organist in chapel, where she stood out among the gray-habited nuns in her navy blue jumper and slightly askew blue veil. She looked about twenty-five, but I’d learned not to trust my eyes when it came to guessing a nun’s age.

Contrition

Contrition