- Home

- Maura Weiler

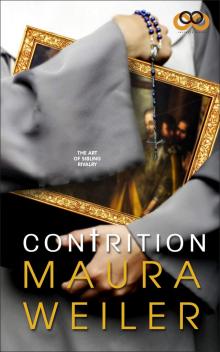

Contrition

Contrition Read online

More praise for Contrition

“In Contrition, Maura Weiler creates a tapestry woven of spirituality, artistic ability, and family bonds. This poignant and riveting debut novel delivers a rich voice and compelling characters. A must-read.”

—MIKE BEFELER, author of Mystery of the Dinner Playhouse

“A haunting, spiritual journey through darkness and light, Maura Weiler’s Contrition tells the story of twin sisters separated at birth, their shared commitment to God and art, and the sorrow and vulnerability each learns about herself as they come to know one another. Moving and bold.”

–JIM RINGEL, author of Wolf

“Contrition is a lively tale of twins separated soon after birth and then reunited in a cloistered monastery in Big Sur. Contrition explores the perils and pulls of art, faith, and fame. Smoking, drinking tabloid writer Dorie McKenna specializes in crafting wacky tell-alls about fake two-headed goats for The Comet, but when she begins to immerse herself in her long-lost sister’s world of silence, self-abnegation, and prayer, she finds genuine stories she doesn’t want to embellish, a call to pursue something higher, and nuns who lead her down a counter-cultural path to happiness.”

—JENNY SHANK, author of The Ringer

Thank you for downloading this Infinite Words eBook.

* * *

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Infinite Words and Simon & Schuster.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

To Christine Taber Your friendship and talent are missed; your inspiration lives on

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Heartfelt thanks:

To my first readers, Ann Buchanan, Michelle Topham, and Louise Weiler, who saw me through multiple “nunumentary” drafts as I separated the detail from the drama; to the writers in my first critique group, Will Baumgartner, Lisa Golloher, Julie Paschen, and Rick Schwartz, who taught me the novel craft; and my second, Sara Alan, Carrie Esposito, Susan Knudten, and Gemma Webster, who taught me the art of emotion.

To Nick Arvin, Mike Befeler, Eleanor Brown, Erika Krouse, Laura McBride, Jim Ringel, Jenny Shank, and Rachel Weaver for their guidance and generosity. To Lighthouse Writers Workshop founders, Andrea Dupree and Michael Henry and their staff, for both the outstanding writing community they foster and the tranquil writing space they provide.

To the teachers who believed in me: Paula Zasimovich Ogurick, Rita Green, and William Krier; and to the one I am still learning from, William Haywood Henderson. To my agents, Sara and Stephen Camilli, and editors, Zane, Charmaine Parker, and everyone at Infinite Words/Simon & Schuster, for their faith in this novel.

To Chad, Gianna, and Aliyah, for the deep joy, frequent laughter and unconditional love that make me whole, and to my parents, Claire and Nick, for their support and tireless enthusiasm. To my extended family and friends for their countless pep talks, feedback on the book, and willingness to listen.

I owe the details of the cloistered tradition to the hospitality of many religious orders who shared their sacred space and often their stories as I researched this novel in California at the Abbey of New Clairvaux, the Carmel of Saint Teresa, the Monastery of the Angels, the Monastery of Poor Clares, the New Camaldoli Hermitage, the Old Mission Santa Barbara, and Saint Andrew’s Abbey, and in Colorado at the Abbey of St. Walburga.

Special thanks to Sister Kathleen Bryant, RSC, both for her discernment seminars and her insightful book, Vocations Anonymous. Additional publications I found helpful included The New Faithful by Colleen Carroll Campbell, St. Benedict’s Rule for Monasteries as translated by Leonard J. Doyle, Nuns as Artists by Jeffrey F. Hamburger, Music of Silence by David Steindl-Rast with Sharon Lebell, and numerous pamphlets provided by the religious communities I visited.

My utmost gratitude goes to my friend, the late painter Christine Taber, who shared her artistic process with me before her untimely death and whose abstract paintings inspired the art descriptions in the novel. This book is for her. And thanks to Bill Turner at the William Turner Gallery for allowing me the space to grieve and write about Christine’s paintings both as they hung in his gallery and for months beyond.

PROLOGUE

I rarely speak now. And I never write. Not after what happened.

A year ago, I wrote too much: sentences that ran across the page with the kind of passion only a hungry, young journalist can muster. Declarations I thought would make a difference.

They made a difference all right. My words of sincere praise led to crushing loss. So I stopped using them. Most slipped away in the silence, but there are a few stubborn ones still demanding a voice.

Today, I feel compelled to pick up my pen and use them up. I have enough words left for that.

CHAPTER ONE

Nuns terrified me with their year-round Halloween costumes and severe shoes. Even after eight years of Catholic school, I still found their built-in piety intimidating. Never mind that I was a twenty-six-year-old woman approaching the convent where my twin sister lived. I may as well have been a ponytail-pulling, seven-year-old being marched to Principal Sister Helen’s office back at Sacred Heart Elementary in Calabasas.

I wondered if Candace, now called Sister Catherine, would be home. Then I remembered that a cloistered nun never left her convent. I wasn’t ready to meet the twin whose existence I’d only recently learned about, but I wanted to see where she lived a life so different from my own. I would drive by, take a look, and leave without ever getting out of the car.

At least that was the plan until I found the top of the driveway impassable. A waterlogged pothole larger than my Jetta stood between the convent and me. The recent rains had been very thorough.

I rolled down my window and peered into the night. The mist kissed my face while the compound’s eight-foot adobe walls blocked my view. I’d have to get out of the car and walk to the wrought-iron gate if I wanted to see anything. I assessed my wanna-be Armani suit and determined that it needed dry cleaning anyway.

As I opened the door and stepped out into the rain, I considered the day’s assignment. As expected, the piece on the unlucky goat that had brought me to Big Sur wasn’t going to be the breakthrough story I’d been looking for to expedite my escape from tabloid hell, but it had brought me to the place I’d been avoiding for the last four months–a convent where my past and future would collide.

• • •

That morning, Phil Stein, editor-in-chief of the West Coast’s premier gossip sheet, The Comet, had picked his way through the paper-strewn, fire hazard of a newsroom and stopped at my friend Graciela’s cubicle.

“Find out more about this two-headed goat, Sanchez,” he ordered, waving the blurry snapshot and accompanying letter in his hand.

Graciela and I shared a look over the low cube wall between our desks. “Find out” was Philspeak for “fabricate.”

“Maybe it talks,” Phil added, skimming the letter.

“Or predicts the stock market?” Graciela said in all seriousness while inhaling a brownie. Reed thin, Graciela functioned, albeit rather spastically, on a pure sugar diet.

“Uh, uh.” Phil shot her down with his trigger finger. “Guinea fowl did that last year.”

“Too bad.” She set aside her snack with effort and picked up the phone.

“Drive up to Big Sur.” Phil hung up Graciela’s phone before she could dial. “Goats give poor phone interviews.”

“Did you say Big Sur?” Graciela looked at me. Even though months had passed since I’d located my twin, she realized I hadn’t met Sister Catherine. “Muy interesante.”

It was interesting, all right. And terrifying. Shortly after my adoptive father passed

away earlier in the year, an estate lawyer had contacted me to disclose that my late biological father was the renowned abstract artist Rene Wagner. Before I could react, he added that my biological mother, an aspiring poet named Lucy Gage, had died giving birth to not one but two babies.

I was a twin. My adoptive parents had told me how my mother died but never mentioned that I had a sister—something they probably didn’t know themselves given that names and most details were withheld in my closed adoption. Absorbing this after being raised as an only child rocked my sense of self much more than learning that my biological father was famous.

In some ways, it was a relief. If the connection many twins describe is real, it explained why I sometimes felt pain without an injury, laughed for no reason, and knew odd facts I hadn’t learned, like where to find the best surfing waves in Malibu. Maybe the urge to find my biological parent—something I felt strongly but had never mustered the courage to pursue—was really the urge to reconnect with my twin.

The Wagner biographies I’d read didn’t mention me or my relinquishment but did say that the hard-drinking Rene raised my sister, Candace, until he died of cirrhosis of the liver when she was seventeen.

I knew there were good reasons why my birth father chose adoption for me and kept my twin. I also knew I was probably better off as a result. But the fact that I didn’t exist to him, at least not on paper, was a permanent punch in the gut.

Candace disappeared from public records shortly after Wagner’s death. It took some sleuthing and called-in favors to learn that she entered the cloistered Monastery of the Blessed Mother in Big Sur after her high-school graduation, later taking the name Sister Catherine and making her solemn vows.

In the last few months, I’d compiled enough information to write my own book about my birth father if I’d wanted to. But writing Wagner’s biography would involve tackling his alcoholism, revealing myself as the child he’d put up for adoption, and meeting the twin he’d kept, none of which I felt ready to do. I’d had a great childhood as Connor and Hope McKenna’s adopted daughter, and I didn’t see the point in dredging up my or Rene Wagner’s past, much less my sister’s. Yes, I was curious about Candace and wanted a relationship with her—maybe too much. What if I overwhelmed her with some irrational belief that she should be the mother, father, and sister I’d never known all rolled into one? I doubted I would be that needy, but until I felt ready to meet her with no expectations at all, it wasn’t worth the risk that I’d freak her out or have her dismiss me as my birth father had.

On the other hand, my coworker couldn’t believe I hadn’t met my twin yet and had no qualms about handing off the goat assignment to help make it happen.

I shook my head at Graciela and mouthed, “Don’t you dare!”

“I’d love to go to Big Sur, Phil, but here’s the thing.” Graciela tapped her watch and ignored me. “It’s almost noon and that’s a twelve-hour round-trip. I can’t leave Sophie in daycare until midnight. Daycare means daytime, comprende?”

“Pesky children.” Phil huffed with a grandfatherly smile.

“Why don’t you send Dorie?” my coworker asked, all enthusiasm. “She likes field trips.”

I shot daggers at Graciela with my eyes. She batted her lashes and made me laugh.

“Fine.” Our editor wheeled around and handed me the farmer’s blurry snapshot and accompanying letter. “Bring a camera, McKenna. Need better pictures.”

“Well, you know you won’t get those from me,” I said. My picture-taking skills ranked among the worst in the newsroom.

“They’ll be good enough.” Phil didn’t bother hiring real photographers since most pictures were digitally altered later.

“How about I interview him on the phone and have him text better photos?” I offered.

“Not gonna work,” Phil said. “He describes himself as technologically challenged.”

“Isn’t Highway One closed from the mudslide damage?” I asked, attempting to switch tactics.

“It reopened last Thursday,” Graciela said, her eyes shining.

I wished I could match her excitement over the possibility of me meeting my sister, but I could barely process it. My birth parents were both dead, yet there was this living person with a direct connection to them whom I could actually talk to if I wanted to. Did the ghosts of our parents follow her around? Did they follow me?

“So there’s nothing keeping me from going to Big Sur.” I scowled and eyed the pack of cigarettes that California state law forbade me from smoking inside the newspaper’s bullpen. “Oh, joy.”

“Surprised.” Phil tilted his head and considered. “Thought you’d jump at the chance to get out of here.”

“Are you kidding?” Normally he’d be right, but today staying put sounded better than driving to a place I’d been avoiding. “I relish every moment I have at the feet of a newspaper god such as yourself.”

“Nice try.” Phil dropped the letter and photo on my desk. “Put in for mileage and take tomorrow morning off to recover.”

The morning off wasn’t a generous gesture on Phil’s part. He didn’t want to pay the overtime.

Still, as assignments went, it wasn’t a bad one. I wasn’t proud of my job, but it paid the bills, though barely. I spent my off hours writing serious articles in hopes of selling them to legitimate newspapers, but so far I hadn’t had a freelance story get noticed by a paper of record. In the meantime, I stuck to mostly animal and alien stories at the tabloid. As long as my subjects couldn’t read or didn’t exist, they couldn’t sue for libel.

• • •

Six hours of driving produced a decidedly one-headed goat with a softball-sized lump above her left ear, but Phil would want to run the story anyway. We’d already covered all the true animal freaks of nature within a 500-mile radius and were scrounging for items until the next breeding season produced a new crop of genetic anomalies.

“That looks painful,” I said, wincing as I scribbled notes in my palm’s-width reporter’s notebook.

“Doesn’t hurt her a bit,” the goat’s gap-toothed owner explained. “Vet says it’s a benign tumor.”

I had to admit that two-year-old Carmie seemed comfortable enough to be bored by the prospect of her imminent fame. I pulled a digital camera from my bag, and did my amateur best to keep my disabled fingers out of the way while I snapped pictures.

I was born with a crippled right hand. The thumb curled under my first two fingers and over the second two, forming an awkward fist. I had mobility in my index and middle digits thanks to multiple infant surgeries, but the others were useless. I’d devised ways to do most everything people with normal hands could do, but photography was a particular challenge.

“Do you think she’ll make the cover?” the farmer asked.

“Depends on how realistic we can make it look in Photoshop. But my editor loves this kind of stuff.”

The farmer threw his head back and crowed in delight.

“Whoo hoo! Wait ’til the guys at the diner see that I got you into The Comet!” he said to the goat as he patted her second “head.” “It’s way better than when Stan Mitchell’s cow was in that stupid feed store ad, huh, girl?”

Carmie nuzzled into his hand, apparently a willing exploitee in her owner’s game of one-upmanship. Or maybe she was simply looking for food.

“Hang on,” the farmer said, pulling a black Sharpie from his pocket and drawing two eyes and a smile on the goat’s lump. He stepped back to admire his handiwork. “Much better.”

“I don’t think it gets much better than this,” I said, gesturing toward the landscape.

I snapped a few more pictures of Carmie and then took a shot of the expansive ocean view from the lush pasture. A light rain tangled crystalline drops in my eyelashes as I admired the sunset. People had told me how beautiful Big Sur was, but words couldn’t capture its graceful splendor. Huge redwoods nestled against mountain cliffs on the east side of Highway One; the ocean crashed against a rocky beach

on the west. Even the soggy evidence of the recent mudslides couldn’t detract from its majesty.

“This is some prime real estate for a goat,” I said.

“Don’t I know it?” The farmer pulled his black cap lower on his forehead as the mist dusted it gray. “I’d build condos but for the zoning laws.”

“I’d buy one.” I could afford an imaginary condo.

Afterward, I started my car, lit a cigarette, and drove into the growing darkness. A couple of miles down Highway One, I saw a large, wrought iron cross and a sign that read “Monastery of the Blessed Mother.” I hadn’t noticed it on the drive up, obscured as it was by a hedge on the south side.

I squeezed the steering wheel and silently cursed Graciela. I hadn’t planned to look up Sister Catherine, a.k.a. Candace Wagner, but now that I was mere yards away, the desire to see where my twin lived overwhelmed me. What did her home look like? What did the home she grew up in look like, for that matter? How would our lives be different if we’d grown up in that place together?

Without thinking, I stubbed out my cigarette, turned my car off the road, and chugged up the steep, switch-backed driveway.

CHAPTER TWO

Walking toward the monastery, I stepped carefully to avoid the muddy patches of ground. Damp salt air rose from waves that spilled onto rocks far below, mingling with the cool rain and heightening the pungency of the anise and fennel that grew along the edge of the pockmarked driveway. I skirted the pothole, arrived at the gate, and peered through the bars. The drizzle and the distance made it impossible to see more than vague outlines of a building. I half considered ringing the nearby doorbell, but gaining entrance would mean interacting with a nun. Before I could decide, a diminutive sister who looked about sixty emerged from the murk carrying a pink umbrella.

A chill crept up my neck. I wanted to bolt, but my legs shook too much to carry me away.

Contrition

Contrition