- Home

- Maura Weiler

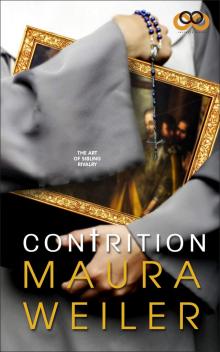

Contrition Page 4

Contrition Read online

Page 4

“Sad but true,” I agreed. Our editor only endorsed whatever we appeared to be against.

“Speak of the devil...” Graciela said without turning around to look. The scent of stale cigar smoke preceded Phil by about ten yards. “Remember, keep up the enthusiasm and you’re home free.”

“That won’t be hard,” I said. It was impossible for me to act nonchalant about a story that mattered to me.

“Got my goat?” Phil asked when he arrived at my cubicle.

“I wish.” I handed him the two-headed goat story fresh from the copy department. He snatched it and began scanning.

“The pictures should be back from photo any minute,” I said.

“Wanted this for today’s edition.” The editor’s eyes advanced down the page.

“Didn’t you get my message about the weather cond—”

“Mmm-hmm. Just stating the facts out of an inflated sense of self-importance.” He flipped to the second page and continued reading. “Next trick: feigning interest in your well-being. Tired?”

“Exhausted, but I stayed overnight at a convent and I think there’s a story there. One of the nuns is an incredible painter and—”

“Can’t use it,” he said.

Graciela struggled to suppress a grin.

“Why not?” I asked, half-smiling myself. “She’s really tal—”

“Don’t care.” Phil flipped to the next page. “My mother paints. Unless this nun paints porn…”

“She does religious subjects.”

“There’s a shocker. Do said subjects cry actual tears? Do they have real, or at least convincingly faked, stigmata?”

“No.” I watched Phil’s anemic interest bleed out of him.

“Then forget it.” The editor tossed the goat story on my desk. “Looks fine. Proof it and get it to layout.”

“But her stuff is amazing,” I said, laying it on for extra insurance. “I think it may be—”

“Got a title? How about ‘Two-Headed Goat Butts Heads with Herself?’” He patted himself on the back. “Use it.”

Graciela’s grin busted out across her face as Phil walked away.

“Nice work, chica,” she said. “Now you’re ready for the big leagues.”

“Yep.” I gulped, suddenly needing that cigarette after all.

• • •

“I don’t see what you’re so hyped about,” Matt, my former boyfriend and current next-door neighbor, said through a mouthful of huevos rancheros on the sunny patio of the Rose Café. Those waiting for tables at our favorite Sunday morning breakfast spot stood ogling other people’s pancakes and snorting with contempt at anyone who lingered too long over emptied plates. “The Comet would never run a serious piece, and even I know the odds on somebody picking it up freelance are way shitty.”

“Thanks for the vote of confidence,” I said over the din of clattering dishes and Sunday chat.

“I just want you to be realistic about your chances.”

“I am. I’m doing it as much to get to know my sister as I am to get published.”

“Well, that makes more sense to me,” he said, shuffling through the stack of newspapers that crowded our table. Matt was the only other person I knew who still liked to read hard copies of the weekend papers. “I just wish you would get to know her on her terms.”

“She’s not really offering any terms,” I said. “So I’m making them up as I go.”

He shrugged, snapped open the Los Angeles Times, and dove in, his bed head hair sticking up over the paper. Sunday was the only day Matt had to catch up on errands and the news of the world. His job as a film production assistant kept him in a sort of suspended animation. The work hours were so insane that the rest of his life got dropped.

“We landed another probe on Titan?”

“A week-and-a-half ago,” I said.

“Really.” He whistled and resumed reading.

We reached that point in our meal where those waiting for a table could justifiably scowl at our indifference to their plunging blood sugar levels. I used my fork to cut off two more bites of my French toast and called for the check. I always ordered soft foods at restaurants so I didn’t have to struggle to use a knife in public.

“Time to go, Mr. Current Events,” I said.

“Yes, Ma’am.”

Matt and I headed for our apartment building. We walked arm-in-arm not because we were in love, though we may have been once and might still be on a good day, but because I had to lead him like a blind man as he continued to read the paper.

Our Venice neighborhood was half-gentrified, half-terrified. The ocean views, art galleries, and multimillion-dollar renovations collided with regular drug deals, tattered homeless wandering the streets, beach hippie culture, and crumbling, rent-controlled apartments like the ones Matt and I occupied.

“Curb,” I warned when we reached a corner.

“Tornado hit South Dakota.” Matt felt for the curb with his foot and stepped up as he folded the newspaper to a new section. “Political crisis in Indonesia.”

Matt had been between films back when I’d moved in across the hall from him two years before. That left us plenty of time to get to know each other and start dating. I tried not to fall too hard for him, sensing that neither his personality nor his profession left room for any real intimacy. When he got his next movie gig three months later, I found myself playing the part of a production widow trying to have a relationship with someone who was either absent or asleep. I hung on for another three months, but it wasn’t working. We broke up, remaining friends and neighbors, sharing newspaper subscriptions and Sunday mornings. I wallpapered over my real feelings as best I could with a confident, bold pattern befitting an independent woman who accepted that the man she loved would never want the same things she did—at least not at the same time.

Having already lost four parents, the idea of building a family both fascinated and freaked me out. I craved the connection, while fearing the possibility that I could lose that new family, too. I wasn’t in a huge hurry to get married and have kids, but I knew, based on prior comments, that Matt was in no rush at all, not to mention that he wasn’t my boyfriend anymore. I would probably need to look elsewhere when I was ready to risk it. In the meantime, I hoped to get to know the one family member I’d just learned I had, if only during short visits in the cloister parlor.

“Wildfires are burning up Florida.” Matt shuffled along and kept reading. “Flooding continues in China.”

When we arrived outside our building, I slipped my arm out from his and left him standing beside the mailboxes just to see what would happen. Thirty seconds passed before he realized where he was and followed me inside.

I managed to fool myself, but nobody else, about my affection for Matt. In the year and a half since we’d broken up, I dated only rarely and always compared other guys to him. Meanwhile, “trust-me” brown eyes and an affable manner made it easy for Matt to meet women in the scant free time he had.

“Earthquake in Afghanistan,” I heard him mutter in the hallway as he opened his apartment door.

Once in a while, he got involved with someone. The potential girlfriend usually bailed after two weeks of Matt’s schedule and I got my best friend back. So in the name of friendship, I led him around by the nose while he eyeballed the paper, but I didn’t feel too bad about leaving him out on the curb.

• • •

“Where’s Evan?” Matt asked an hour later when I let myself into his apartment. He sat straight up from the couch where he’d been lying on what I hoped was a pile of clean laundry. His staring eyes were open, but he wasn’t awake. “I’ve got to get him to the set!”

“Shhh, you’re okay. It’s Sunday.” I helped him lie down again. “You and Evan have the day off.”

Evan Cole was the twenty-seven-year-old star of the action movie Matt was working on. Matt had been assigned to be the actor’s personal production assistant. Evan was low maintenance, but Matt took his job seriously in h

opes of impressing the producers and promoting his own fledgling directing career.

I folded a sweatshirt and positioned it behind Matt’s head. We had planned to play tennis, but the man clearly needed his rest. I scanned his bachelor-chic apartment, which, despite a weight bench occupying the space where a kitchen table should be and a home theater set-up worth more than the rest of the contents combined, was still cozier than my own apartment across the hall.

The scuttled tennis game meant my whole Sunday now stretched before me in open invitation. I decided to drive up to Big Sur. It wasn’t Visiting Sunday at the convent, but then I didn’t feel ready to see Catherine again anyway. Instead, I would photograph the Madonna and Child so I could ask my art-dealer friend Trish’s opinion of it and have a copy for myself. The warm feeling I got whenever I looked at the Virgin Mary’s expression was something I wanted to have available at all times. Was that how Catherine imagined our mother?

CHAPTER FIVE

Arriving at the convent, I headed straight for the visiting room as the songs of five o’clock Vespers floated out of the chapel. I tried not to worry when the canvas wasn’t on the parlor wall. When it wasn’t in Sister Teresa’s nearby bathroom hiding place either, panic set in just beneath my rib cage. I paced the courtyard for eight chain cigarettes waiting for Vespers to end and was in the chapel the moment they did.

“I don’t think she took it down to work on it this time.” Sister Teresa collected and slid the hymnals down one of the public pews toward me.

“Well, that’s a relief. At least it hasn’t been altered,” I said, stacking the hymnals in a pile at the end of the row. “But where is it? She didn’t change her mind and sell it to someone else, did she?”

“Not exactly, no.” The extern paused, as if unsure of how to break the news to me. “My guess is that she gave it away.”

“She what?” Panic turned to fury, dropping down from my rib cage to burn a hole in my belly. “But why would she give it to someone else when I would have been happy to pay at least what I could afford for it?”

I forgot about the incoming hymnals and unconsciously tapped a cigarette out of the pack, further agitated when I realized I couldn’t smoke it inside.

“Oh, she didn’t give it to a person.” Teresa approached and gathered the neglected books. “She gave it back to God.”

I dropped the cigarette and looked at her, uncomprehending.

“Art supplies are pricey.” The nun picked up my cigarette and whisked the unlit tobacco under her nose with what looked like lust if I hadn’t known better. “We can’t keep up with the demand at the rate Sister Catherine goes through them, so she recycles canvases.”

“As in paints over them?”

Sister Teresa nodded and handed the cigarette back to me. “I kept that one around longer than usual, but she always finds my hiding places eventually.”

I sat down in the front pew, speechless but not silent, as I burst into tears. Intellectually, I knew an article about an artist who blithely destroyed her own work was that much more compelling. Emotionally, I’d formed a personal bond with the painting. My family that never was had just lost an heirloom.

“I feel your pain.” Sister Teresa sat beside me and put a hand on my shoulder. “We strive for detachment from material things here. Sister Catherine gives us a chance to practice that skill more than some of us have a mind to. Can’t say I’ve gotten very good at it.”

“I’m sorry.” I wiped my eyes with the back of my strong hand. “It’s just been a long time since I’ve gotten that excited about anyone, I mean, anything. I can’t believe it’s gone.”

“Do you remember what it looked like?”

“More or less.”

“Then it’s still here.” The nun tapped her temple. “And here.” She touched her heart.

“But what if I forget?” I was in no mood for sentimentality now.

“Then God will put something better in its place.”

I was still unconvinced. We sat there for several minutes before Sister Teresa spoke again.

“Come with me.” The extern stood and led me out of the chapel, her keys jangling out the cadence of her stride.

“I don’t get it.” I rose and followed the nun into the courtyard. “How could an artist bear to lose her own work, much less destroy it herself?”

“From what I can figure, Sister Catherine values the act of painting, not the outcome. The creation process is her method of prayer, a direct appeal to God, who replies in colors and shapes. Once their conversation is over, Catherine considers the finished piece incidental.”

“But that’s tragic.”

“Maybe,” Teresa said as we passed several of the closed courtyard doors. “Sister Catherine doesn’t show or sell her paintings because she doesn’t want to be given the credit for them. In order to keep the channel clear for God to work through her, she paints as often as possible, even, and sometimes especially, if that means recycling canvases.”

I found it all very noble and maddening at the same time. “It’s selfish to squander such an inspired vision of God.” I stomped along in my heavy-soled loafers. “How anyone with such a gift could just throw it away is beyond me.”

“Who’s to say she’s throwing it away?” Teresa stepped lightly in her bare feet. “Maybe God is audience enough.”

“What kind of God would ask an artist to destroy a part of herself?”

“I don’t think God made that request so much as Sister Catherine took it upon herself to reuse canvases.” Sister Teresa led the way to the parlor door. “At any rate, faith and love often result in some sort of personal sacrifice.”

“Personal sacrifice, sure, but what about everyone else? People would be inspired by Sister Catherine’s work. If it’s not hers to take credit for, then why does she get to decide what happens to it?”

“Who do you think should decide?”

I couldn’t answer that.

We entered the parlor.

“Make yourself at home.” The nun gestured to a chair. “I’ll be back in a jiffy.”

Teresa disappeared through the cloister door. I sat and waited. The Shaker chair was even more uncomfortable than the church pew. Scanning the walls for more paintings, I found only picture windows and a framed religious print of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. It seemed heartless of Him to reclaim the painting just as it was restoring my faith in, well, something.

Ten minutes later, Sister Teresa reentered, this time on the cloistered side of the room. From behind the bars, she revealed a canvas she’d hidden under the folds of her habit.

“Sorry it took me so long. I had to find one small enough to smuggle.”

I jumped up and put my face to the grille so the bars didn’t obscure my view as Sister Teresa pulled out the unframed oil painting depicting the Annunciation. At twelve-by-eighteen inches or so, it was much smaller than the Madonna and Child. Mary knelt before the Angel Gabriel, whose silken wings fluttered against a dreamscape where soft, gray brushstrokes suggested fading fireworks on a misty night, melting away into the gauzy beauty of a blackened sky over a depthless ocean. It didn’t take me long to find what I was looking for: the angel held his hand over Mary in the gesture of blessing that resembled my handicap.

The painting triggered both my secular and spiritual sensibilities. The sanctity of the scene transcended religious fervor and rested in tranquility. I saw the fearsome news that she would bear the Son of God reflected in the Virgin’s eyes, yet her open-armed posture was one of acceptance. My recent distress disappeared and a feeling of peace washed over me.

My eyes moved from the painting to Sister Teresa, who nodded in recognition of our mutual awe.

“Would you mind if I took some pictures?” I pulled out my digital camera.

“I suppose that would be all right, provided they’re only for your personal use. Mind you don’t get me in the photo—my hair’s a mess.” Teresa winked and held up the painting for my clicking camera.

�

��I wasted a lot of valuable class time in grammar school wondering what the nuns’ hair looked like under their veils,” I admitted.

“Those were sisters. Only cloistered religious are called nuns. My hair is wash-‘n-go short, if you must know. Whom should I fix it for?”

“Sometimes I wish I wore a veil.” I pushed a long blonde strand out of my eyes.

“Join us and make bad hair days a thing of the past. When do you feel the call most strongly?”

“The call to what? Cut my hair short?”

“To a religious vocation.”

“Oh, God, never,” I spat out and then cringed, wanting to chew up my words and swallow them again. “I mean, never before now. I hope that’s not a bad thing. I just didn’t see myself that way until uh, the other night in the rain.”

I took pictures faster.

“I see.” Sister Teresa glossed over my abuse of God’s name and focused on my answer. “That’s nothing to be concerned about. We all hear the call in God’s good timing.”

“Last picture.” I snapped it. “Thanks.”

“My pleasure.” A visibly relieved Teresa lowered the painting.

“How did you hear the call?” I asked.

“I felt drawn to the church from my childhood on.” The nun set the painting down and shook out her weary arms. “My mother was quite religious herself and thrilled that I tried to be good and holy. Until I said I wanted to become a cloistered nun, that is. Then she wrote to the Pope and told him to talk me out of it.”

“Really? Why?”

“Despite Mary’s Immaculate Conception, my mother was reasonably sure my becoming a Bride of Christ wasn’t going to produce any grandchildren for her. Plus, she wouldn’t see me much if I entered the cloister, and I wouldn’t be around to take care of her in her old age. So anxiety played a big part.”

“What did you do?”

Contrition

Contrition